RESEARCH

|

My research focuses on what leads to and motivates

destructive behaviours. |

|

To examine this, I study emotions, antisociality, and psychopathology in children and youth. |

SELECTED PAPER Summaries

For a full list, see my ResearchGate page. Illustrations and figures are created by me, see more of my art here.

Genetic-environment interactions affect youth antisocial behavior?

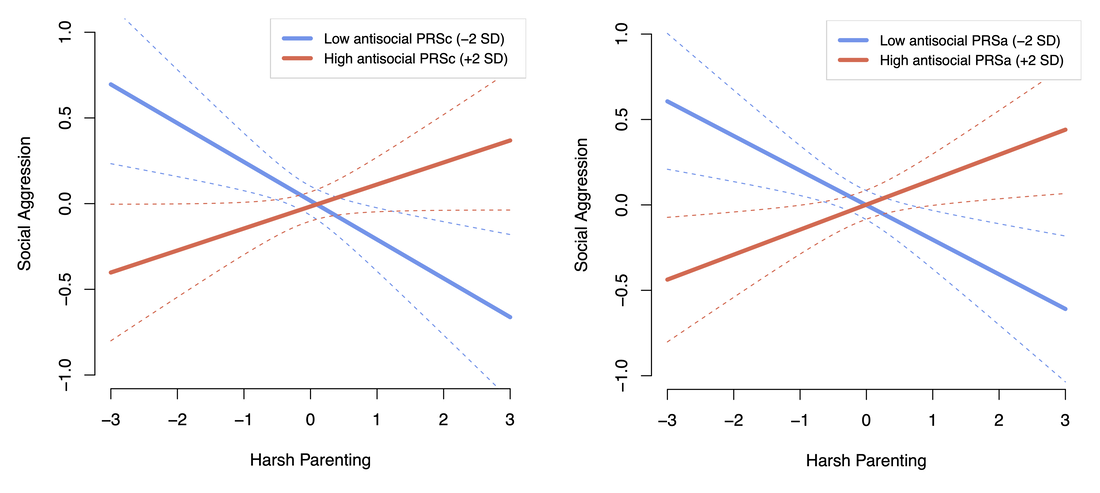

In a longitudinal study (N = 721), we assessed how genetic risk for antisociality (via two polygenetic risk scores; PRSa,c) and hostile environments (school violence, harsh parenting) related to stable and unstable forms of antisocial behavior (nonaggressive conduct problems, physical aggression, social aggression) across adolescence (ages 13, 15, and 17 years).

Harsh parenting, violence at school, and antisocial genetic risk were all independently associated with stable forms of antisocial behavior. We also found a consistent genetic-environment interaction specific to late adolescence:

Harsh parenting, violence at school, and antisocial genetic risk were all independently associated with stable forms of antisocial behavior. We also found a consistent genetic-environment interaction specific to late adolescence:

- Higher genetic risk for antisociality: harsher parenting was associated with increased social aggression (red lines)

- Lower genetic risk for antisociality: harsher parenting was associated with decreased social aggression (blue lines)

Interestingly, each genetic risk score (PRSa and PRSc) showed the same genetic-environment interaction, despite each explaining separate portions of antisocial behavior. Genetic risk scores were not meaningfully correlated with one another likely due to one being derived from a primarily child sample (PRSc), while the other from a largely adult sample (PRSa).

IMPLICATIONS: Harsher parenting was linked to elevated stable antisocial behaviors across adolescence. However, shifts in social aggression in late adolescence were partially explained by a consistent genetic-environment interaction (~8% of variance).

Late adolescents considered more susceptible to antisociality may respond to harsh parenting by mirroring that emotional hostility when interacting with peers. Alternately, youth less susceptible to antisociality may respond to harsh parenting in the opposite way: reducing their social aggression (i.e., abstaining from emotional bullying, isolating others, damaging relationships). Perhaps those with lower genetic risk for antisociality are more socially sensitive individuals, who withdraw from all types of social interactions (good and bad) when they feel attacked.

These interactions may only emerge in late adolescence as youth overall become better at inhibiting their base impulses, making those that cannot control their behavior easier to identify as socially divergent. More research is needed to test this hypothesis. These findings are also correlational so we cannot say for certain it is the environment that causes these changes in behaviour, it could be the other way around or a third factor.

Together this suggests that youth may respond to the same challenging environment in opposite ways depending on their susceptibility to that stressor.

Acland, E. L., Pocuca, N., Paquin, S., Boivin, M., Ouellet-Morin, I., Andlauer, T. F. M., Gouin, J. P., Côté S. M., Tremblay R. E., Geoffroy, M. & Castellanos-Ryan, N. (2024). Polygenic risk and hostile environments: Links to stable and dynamic antisocial behaviors across adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942400004X (Open access article).

IMPLICATIONS: Harsher parenting was linked to elevated stable antisocial behaviors across adolescence. However, shifts in social aggression in late adolescence were partially explained by a consistent genetic-environment interaction (~8% of variance).

Late adolescents considered more susceptible to antisociality may respond to harsh parenting by mirroring that emotional hostility when interacting with peers. Alternately, youth less susceptible to antisociality may respond to harsh parenting in the opposite way: reducing their social aggression (i.e., abstaining from emotional bullying, isolating others, damaging relationships). Perhaps those with lower genetic risk for antisociality are more socially sensitive individuals, who withdraw from all types of social interactions (good and bad) when they feel attacked.

These interactions may only emerge in late adolescence as youth overall become better at inhibiting their base impulses, making those that cannot control their behavior easier to identify as socially divergent. More research is needed to test this hypothesis. These findings are also correlational so we cannot say for certain it is the environment that causes these changes in behaviour, it could be the other way around or a third factor.

Together this suggests that youth may respond to the same challenging environment in opposite ways depending on their susceptibility to that stressor.

Acland, E. L., Pocuca, N., Paquin, S., Boivin, M., Ouellet-Morin, I., Andlauer, T. F. M., Gouin, J. P., Côté S. M., Tremblay R. E., Geoffroy, M. & Castellanos-Ryan, N. (2024). Polygenic risk and hostile environments: Links to stable and dynamic antisocial behaviors across adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942400004X (Open access article).

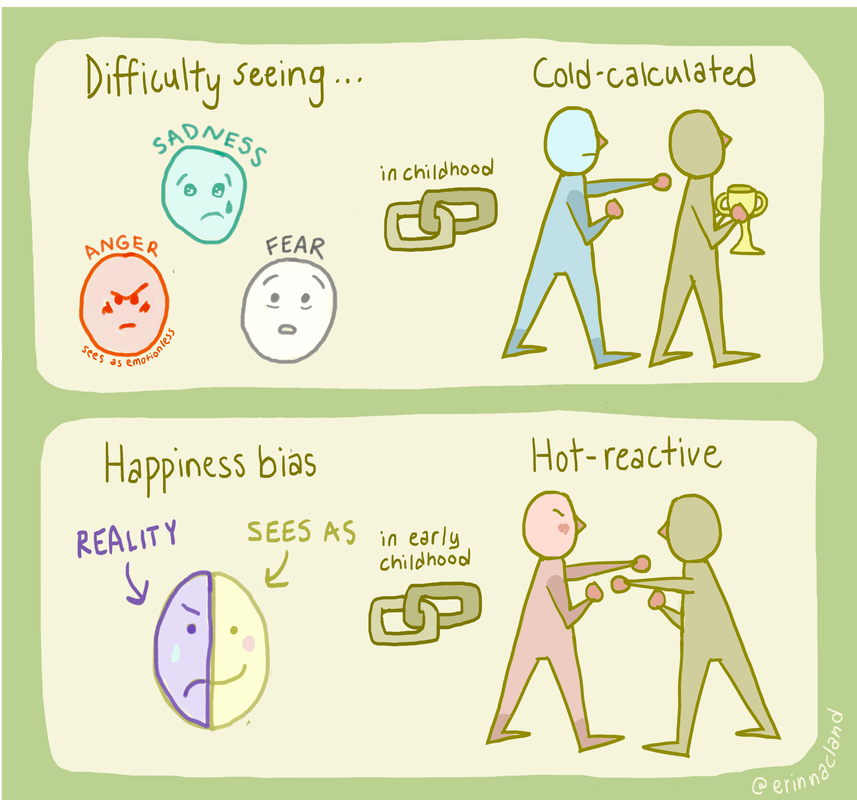

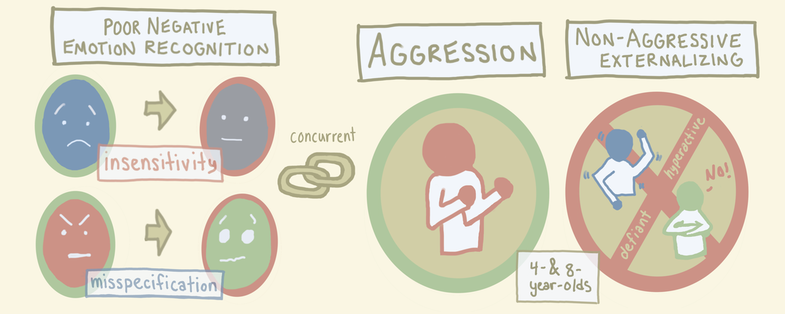

How is emotion recognition tied to cold-calculated vs. hot-reactive aggression?

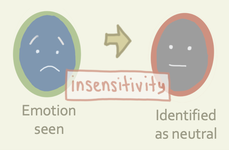

In two independently collected samples of children, we found that more difficulty identifying expressions of fear, anger, and sadness in others was consistently related to using goal-focused (also known as cold-calculated) aggression. Fear and anger associations with goal-focused aggression were stronger in early (ages 4-6) and middle childhood (ages 8-9), respectively. Interestingly, we found that how they misrecognised angry expressions mattered. Goal-focused aggression was tied to thinking angry expressions looked emotionless (i.e., anger insensitivity), rather than mixing up anger for another emotion.

|

On the other hand, we thought that reactive aggression—which is typically associated with a hot-headed temperament—would link to seeing more anger in faces regardless of whether they were actually angry (i.e., an anger bias). But surprisingly, that isn’t what we found.

Instead, thinking negative expressions looked happy (i.e., a happiness bias) was consistently linked to more reactive aggression, but only in early childhood. Findings were consistent in both samples. IMPLICATIONS: Children who engage in more cold-calculated aggression have greater difficulty seeing when others are in distress and are less sensitive to threat cues. Difficulty seeing that they've upset someone may allow them to stay calm and goal-focused in intense situations, making it easier for them to harm others to get what they want. |

Young children exhibiting hot-reactive aggression may be particularly sensitive to rewarding emotions leading them to see happiness when it isn’t there. Trouble figuring out the valence of an emotion (mistaking negative for positive emotions) could also be causing social blunders that result in conflict. Lastly, this study was correlational, meaning we can’t say for sure whether reduced emotion recognition causes aggression in children, only that those two things seem to hang together.

Acland, E., Peplak, J., Suri, A., & Malti, T. (2023). Emotion recognition links to reactive and proactive aggression across childhood: A multi-study design. Development and Psychopathology, 1-12. https://doi.org/0.1017/S0954579423000342 (Open access article). The illustration and excepts of this summary were adapted from an article we wrote for The Conversation Canada.

Acland, E., Peplak, J., Suri, A., & Malti, T. (2023). Emotion recognition links to reactive and proactive aggression across childhood: A multi-study design. Development and Psychopathology, 1-12. https://doi.org/0.1017/S0954579423000342 (Open access article). The illustration and excepts of this summary were adapted from an article we wrote for The Conversation Canada.

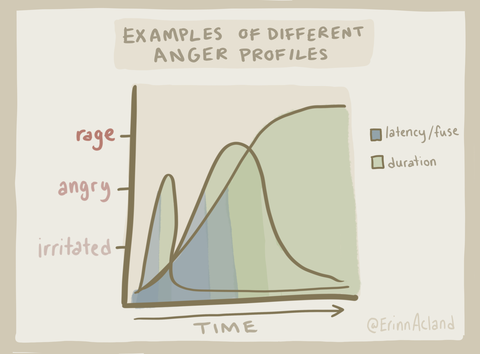

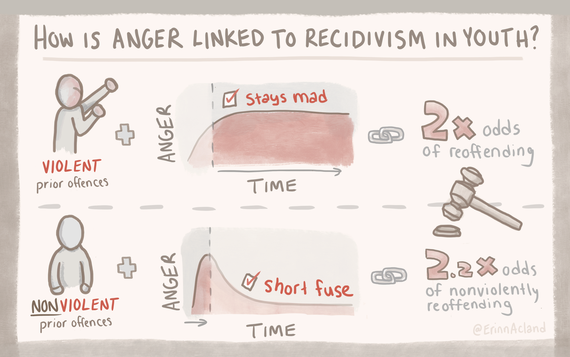

How is anger linked to violence and recidivism in youth?

|

In a court-provided sample of justice system involved youth (N = 548), self-reported anger over the last few months did not relate to whether youth reoffended within two years. This is important information for courts to know given that many juvenile risk assessments include items measuring youths’ anger/irritability (e.g., YLS/CMI). However, characteristics of anger (i.e., fuse vs. duration) were important for their (re)offending behaviour. Among youth with a history of violent offending, reporting prolonged anger was linked to twice the likelihood of reoffending within 2 years. Alternatively, among youth who had a history of only nonviolent offences, reporting a short fuse was associated with being 2.2 times as likely to continue nonviolently offending. Gender and age (11 to 18 years) were controlled and did not moderate these relations.

|

|

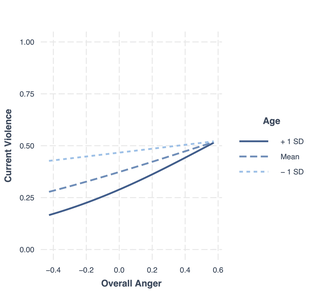

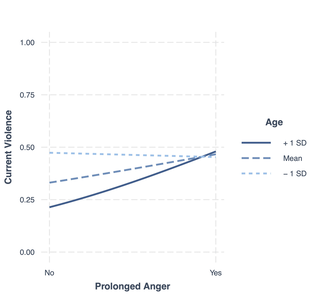

Figures 1 & 2. Overall and prolonged self-reported anger and current violent behaviour by age in justice-involved youth. Mean age = 14.9 years, standard deviation (SD) = 1.40. Higher overall anger and/or a short anger fuse was linked to current violence in justice-involved youth. Overall anger was especially tied to current violence in youth age ~14 and older, and prolonged anger was only related to current violence in youth age ~14.5 and older. |

|

IMPLICATIONS: There may be two youth anger profiles that are about twice as likely to reoffend compared to their low-anger counterparts: prolonged anger, serious offenders, and short-fuse, non-violent offenders. The first may represent a brooding youth capable of violence who also tends to engage in non-violent offences (like stealing). The second may represent a quick-tempered youth who tends to act on their emotions with little forethought, but it less likely to commit serious crimes. This latter repeat-offender type may be more likely to desist as they age, as emotion regulation improves with age and less serious youth offenders tend to desist offending in adulthood.

|

Lastly, different characteristics of anger matter more or less depending on youths' age. Further research is still needed to replicate and build on the limited findings in this area.

Acland, E. L. & Cavanagh, C. (2022). Anger, violence, and recidivism in justice system involved youth. Justice Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2022.2028882. View full-text accepted manuscript here. Illustrations and excerpts of this summary are from my article on this paper published in The Conversation Canada.

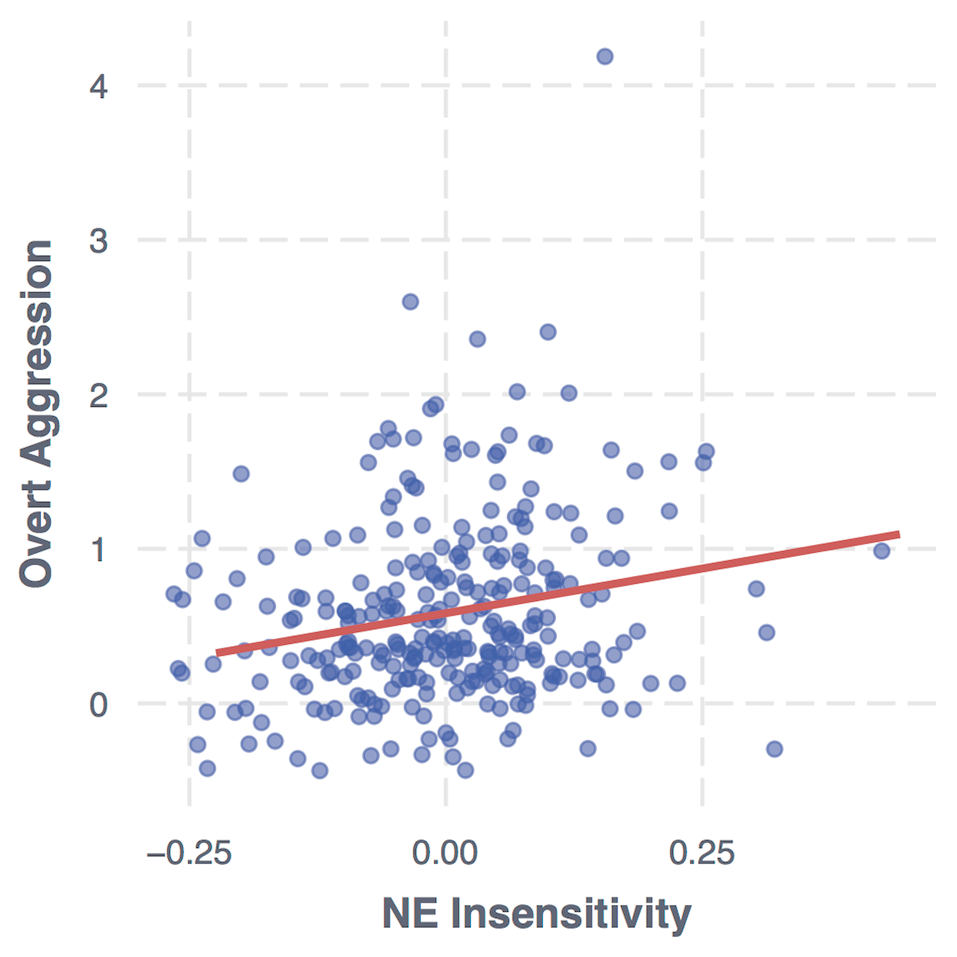

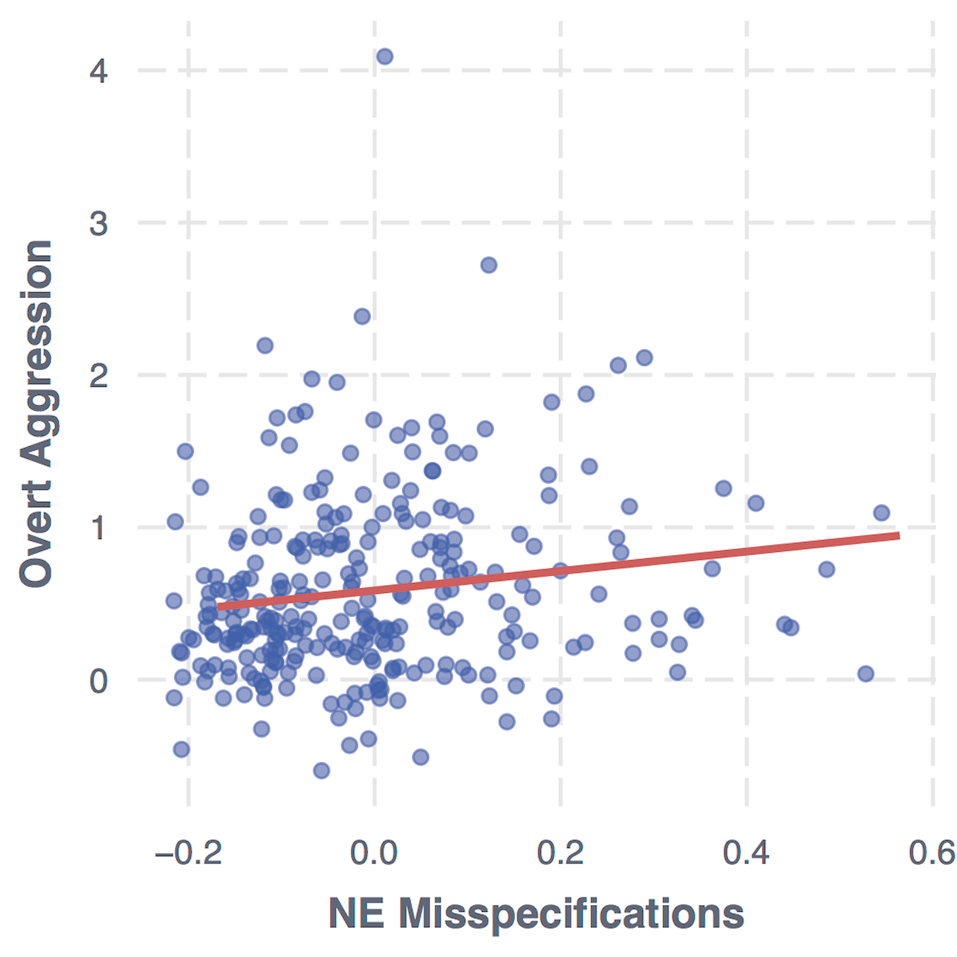

Is emotion recognition uniquely linked to aggression in children?

|

Figures 1 & 2. Negative emotion (NE) insensitivity and mispecification's relation to concurrent overt (i.e., verbal/physical) aggression in 4- and 8-year-olds. Age, gender, verbal ability were controlled. Jitter (0.05) was added to points for improving visibility of point density. NE scores are mean-centered. |

Acland, E. L., Jambon, M., & Malti, T. (2021). Children's emotion recognition and aggression: A multi-cohort longitudinal study. Aggressive Behavior, 1– 13. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21989. Full-text available here.

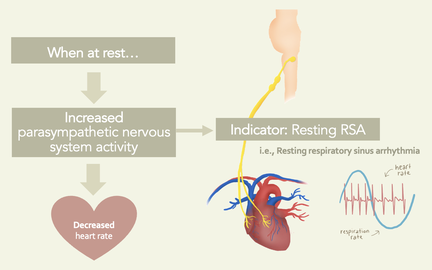

How is parasympathetic nervous system activity linked to prosociality in children?

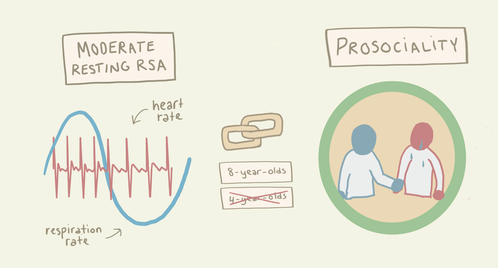

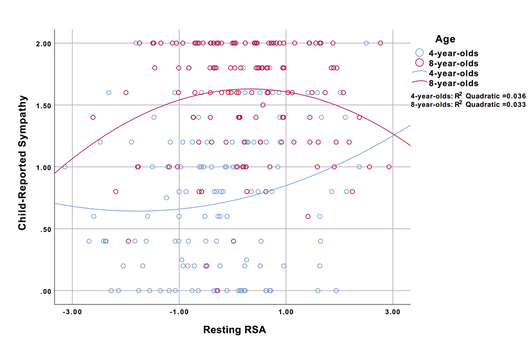

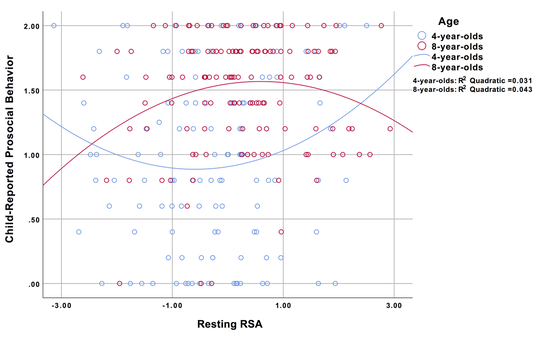

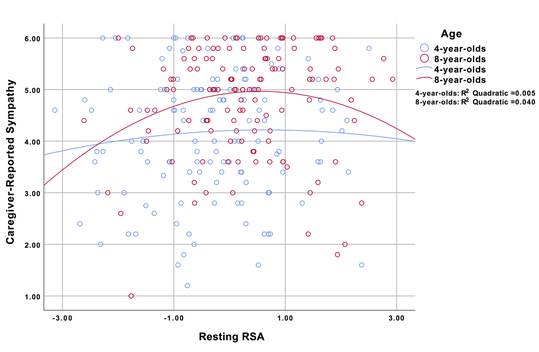

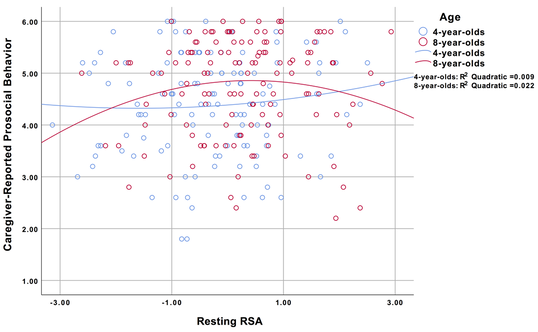

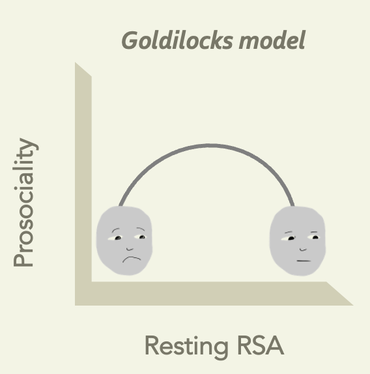

We found a goldilocks relation between children's ‘rest and digest' system (i.e., parasympathetic nervous system) and their prosociality (N = 300). Children with moderate levels of parasympathetic system activation had increased sympathy and prosocial behaviours (e.g., sharing). However, this was only the case for children in middle childhood, not early childhood. Parasympathetic system activation was indicated by children resting respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA).

Figures 1, 2, 3, & 4. Resting RSA and child- and caregiver-reported sympathy and prosocial behaviour for 4- and 8-year-olds. RSA is mean-centered.

|

IMPLICATIONS: Children in middle childhood with under- or over-activation of their parasympathetic nervous system at rest are less prosocial. Those with over-activation of the 'rest and digest' system may be overly serene in the presence of a distressed other, reducing their ability/motivation to feel for and help others. Alternatively, 'under-activation' may be related to difficulty regulating one's own distress when confronted by a distressed other. Further research is needed to explore this theory. Resting RSA has been found to increase with age, thus its influence on behaviour may increase as children age. This would explain why we did not find consistent results in early childhood. |

Acland, E. L., Colasante, T., & Malti, T. (2019). Respiratory sinus arrhythmia and prosociality in childhood: Evidence for a quadratic effect. Developmental Psychobiology, 61(8), 1146-1156. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21872. Full-text available here.